Sponges

Sponges are the most pre historic multicellular organisms that have no proper organs. All members of this phylum are permanently attached to another surface, such as rocks, corals, or shells. A wide range of forms are characterized by their differences in shape and composition. All sponges have a definite skeleton which provides a framework that supports the animal,others are made up of spongy material known as spongin. Sponges are capable of growing into a new individual from even the tiniest body fragment. All sponges feed by filtering tiny plankton. The process of sexual reproduction requires the production and release of large numbers of male sperm cells that are then let out in a form of a dense cloud. By currents the sperm travels and some enter another sponge of the same species. In there the sperm would get trapped in by the choa nocytes from where they will be taken to a special egg chamber. The fertilized egg then goes througha process of division and transformation, developing into a flagellated embryo known as an amphiblastula. when that process is over then the parent sponge releases it and will be carried away by the water currents. Sponges can also reproduce asexually, in which a new sponge developes from an out growth of the parents organism.

Sponges are the most pre historic multicellular organisms that have no proper organs. All members of this phylum are permanently attached to another surface, such as rocks, corals, or shells. A wide range of forms are characterized by their differences in shape and composition. All sponges have a definite skeleton which provides a framework that supports the animal,others are made up of spongy material known as spongin. Sponges are capable of growing into a new individual from even the tiniest body fragment. All sponges feed by filtering tiny plankton. The process of sexual reproduction requires the production and release of large numbers of male sperm cells that are then let out in a form of a dense cloud. By currents the sperm travels and some enter another sponge of the same species. In there the sperm would get trapped in by the choa nocytes from where they will be taken to a special egg chamber. The fertilized egg then goes througha process of division and transformation, developing into a flagellated embryo known as an amphiblastula. when that process is over then the parent sponge releases it and will be carried away by the water currents. Sponges can also reproduce asexually, in which a new sponge developes from an out growth of the parents organism.Cnidarians

Cnidarians all share two main characteristics, one being radial symmetry and the other tentacles with stinging cells. Radial symmetry is when the organism can be divided into identicle pieces, an organism with radial symmetry lacks a head. Their specialized stinging cells are used for defense and capturing their preys.these stinging cells are known as cnidocytes, they’re especially abundant along the tentacles. Cnidarians have features that sponges lack on. One such feature is presence of the gastrula stage during embryonic development.

Cnidarians all share two main characteristics, one being radial symmetry and the other tentacles with stinging cells. Radial symmetry is when the organism can be divided into identicle pieces, an organism with radial symmetry lacks a head. Their specialized stinging cells are used for defense and capturing their preys.these stinging cells are known as cnidocytes, they’re especially abundant along the tentacles. Cnidarians have features that sponges lack on. One such feature is presence of the gastrula stage during embryonic development. Special Exhibition-Coral Reefs

A coral polyp is a tubular saclike animal with a central mouth surrounded by a ring of tentacles. The end opposite the tentacles, called the base, is attached to the substrate. Depending on the species, coral polyps may measure less than an inch to several inches in diameter. Coral colonies also vary in size. Some corals form only small colonies. Others may form colonies several feet high. Star coral colonies reach an average height of 10 to 13 ft. Tentacles are for defense and for moving food to the mouth. Depending on the subclass, a coral polyp's tentacles are arranged in multiples of six or eight. The tentacles contain microscopic stinging capsules called nematocysts. A nematocyst is a bulbous double-walled structure containing a spirally folded, venom-filled thread with a minute barb at its tip. A tiny sensor projects outside the nematocyst. When the sensor is stimulated physically or chemically, the capsule explodes and ejects the thread with considerable force and speed. The barb penetrates the victim's skin and injects a potent venom.

Special Exhibition- Box Jellyfish

Box jellyfish belong to the class Cubozoa, and are not a true jellyfish (Scyphozoa), although they show many similar characteristics. The bell or cube shaped jellyfish has four distinct sides, hence the box in the name. When people talk about the extremely dangerous Australian box jellyfish they refer to the species Chironex fleckeri. This is the largest box jellyfish species. The other species that is known to have caused deaths is Carukia barnesi, commonly called Irukandji. This one is a tiny jellyfish, only about thumbnail size. I talk about Irukandji here. There are other species and not all are poisonous. (From here on, if I say box jellyfish, I am referring to Chironex fleckeri.) A fully grown box jellyfish has a respectable size: it measures up to 20cm along each box side (or 30 cm in diameter), and the tentacles can grow up to 3 metres in length. Its weight can reach 2 kg. There are about 15 tentacles on each corner, and each tentacle has many thousand stinging cells (nematocysts). The stinging cells are activated by contact with certain chemicals on the surface of fish, shellfish or humans. Box jellyfish are transparent and pale blue in colour, which makes them pretty much invisible in the water. So much so that for years nobody knew what was causing swimmers such excruciating pain, and sometimes killed them. The box jellyfish propels itself forward in a jet like motion and can reach three to four knots, that's 1.5 to 2 metres per second. (True jellyfish in contrast rather drift.) Box jellyfish can see. They have clusters of eyes on each side of the box. Some of those eyes are surprisingly sophisticated, with a lens and cornea, an iris that can contract in bright light, and a retina. Their speed and vision leads some researchers to believe that box jellyfish actively hunt their prey, others insist they are passive opportunists, meaning they just hang around and wait for prey to bump into their tentacles. They certainly are very good at avoiding even tiny objects and probably at least try to avoid humans, too. Box jellyfish venom is very different from the venom of the true jellyfish. More on the venom and its effects below. Chironex fleckeri have caused at least 63 deaths in Australia since 1884.

Flatworms

Flatworms also have a sac body plan, meaning they have one opening that functions as both a mouth and an anus. However, flatworms are bilaterally symmetrical, and have three germ layers. Having three germ layers allows for greater tissue specialization, giving flatworms specialized digestive systems, excretory systems, reproductive systems, and nervous systems, which are exemplified by the Planaria, a heterotrophic free-living flatworm.

Special Exhibition- Parasitic Flatworms

Flatworms that are parasitic on humans fall into two categories, flukes and tapeworms. Due to the environment that they live, in a gut of a human, these flatworms have an anatomy different that a planaria. Generally, a parasitic flatworm will have a reduced digestive system and a more complex reproductive system and life cycle. Also, parasitic flatworms will usually have hooks on the scolex (anterior region) to attach it to the wall of the gut, and they have an extra outer covering (glycocalyx) to protect it from being digested. When a flatworm reproduces, the eggs are passed out with feces. When consumed by another host the life cycle continues.Flukes and tapeworms can infect many different animal hosts. They will usually have two each per life cycle, one when sexually mature, which is called the primary host, and a secondary host in which the eggs mature to larvae.

Flatworms that are parasitic on humans fall into two categories, flukes and tapeworms. Due to the environment that they live, in a gut of a human, these flatworms have an anatomy different that a planaria. Generally, a parasitic flatworm will have a reduced digestive system and a more complex reproductive system and life cycle. Also, parasitic flatworms will usually have hooks on the scolex (anterior region) to attach it to the wall of the gut, and they have an extra outer covering (glycocalyx) to protect it from being digested. When a flatworm reproduces, the eggs are passed out with feces. When consumed by another host the life cycle continues.Flukes and tapeworms can infect many different animal hosts. They will usually have two each per life cycle, one when sexually mature, which is called the primary host, and a secondary host in which the eggs mature to larvae.Special Exhibition- Planaria

Planaria are non-parasitic flatworms of the biological family Planariidae, belonging to the order Seriata. Planaria are common to many parts of the world, living in both saltwater and freshwater ponds and rivers. Some species are terrestrial and are found on plants in humid areas. These animals move by beating cilia on the ventral dermis, allowing them to glide along on a film of mucus. Some move by undulations of the whole body by the contractions of muscles built into the body wall. They exhibit an extraordinary ability to regenerate lost body parts. For example, a planarian split lengthwise or crosswise will regenerate into two separate individuals. The size ranges from 3 to 12 mm, and the body has two eye-spots (also known as ocelli) that can detect the intensity of light. The eye-spots act as photoreceptors and are used to move away from light sources. Planaria have three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), and are acoelomate (i.e. they have a very solid body with no body cavity). They have a single-opening digestive tract, consisting of one anterior branch and two posterior branches in freshwater planarians. Because of this three-branched organization, freshwater flatworms are often referred to as triclad planarians.The most frequently used in the high school and first-year college laboratories is the brownish Dugesia tigrina. Other common varieties are the blackish Planaria maculata and Dugesia dorotocephala. Recently, however, the species Schmidtea mediterranea has emerged as the species of choice for modern molecular biological and genomic research due to its diploid chromosomes and existence in both asexual and sexual strains. Recent genetic screens utilizing double-stranded RNA technology have uncovered 240 genes that affect regeneration in S. mediterranea. Interestingly, many of these genes are found in the human genome.It should be noted that the term "planaria" is most often used as a common name. It is also the name of a genus within the family Planariidae. Sometimes, it also refers to the genus Dugesia.

Planaria are non-parasitic flatworms of the biological family Planariidae, belonging to the order Seriata. Planaria are common to many parts of the world, living in both saltwater and freshwater ponds and rivers. Some species are terrestrial and are found on plants in humid areas. These animals move by beating cilia on the ventral dermis, allowing them to glide along on a film of mucus. Some move by undulations of the whole body by the contractions of muscles built into the body wall. They exhibit an extraordinary ability to regenerate lost body parts. For example, a planarian split lengthwise or crosswise will regenerate into two separate individuals. The size ranges from 3 to 12 mm, and the body has two eye-spots (also known as ocelli) that can detect the intensity of light. The eye-spots act as photoreceptors and are used to move away from light sources. Planaria have three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), and are acoelomate (i.e. they have a very solid body with no body cavity). They have a single-opening digestive tract, consisting of one anterior branch and two posterior branches in freshwater planarians. Because of this three-branched organization, freshwater flatworms are often referred to as triclad planarians.The most frequently used in the high school and first-year college laboratories is the brownish Dugesia tigrina. Other common varieties are the blackish Planaria maculata and Dugesia dorotocephala. Recently, however, the species Schmidtea mediterranea has emerged as the species of choice for modern molecular biological and genomic research due to its diploid chromosomes and existence in both asexual and sexual strains. Recent genetic screens utilizing double-stranded RNA technology have uncovered 240 genes that affect regeneration in S. mediterranea. Interestingly, many of these genes are found in the human genome.It should be noted that the term "planaria" is most often used as a common name. It is also the name of a genus within the family Planariidae. Sometimes, it also refers to the genus Dugesia.Roundworms

Roundworms (phylum Nematoda) are a tube-within-a-tube body plan. That is, unlike the Platyhelminthes and Cnidarians which have a single opening functioning as a mouth and an anus, the Nematodes have a separate mouth and anus. This design does allow for specialization of digestive organs, but Nematodes simply have a gut. Sexual reproduction will typically occur between separate sexes, with internal fertilization, and eggs laid for young.

Roundworms (phylum Nematoda) are a tube-within-a-tube body plan. That is, unlike the Platyhelminthes and Cnidarians which have a single opening functioning as a mouth and an anus, the Nematodes have a separate mouth and anus. This design does allow for specialization of digestive organs, but Nematodes simply have a gut. Sexual reproduction will typically occur between separate sexes, with internal fertilization, and eggs laid for young.Annelids

The annelids include animals such as the earthworms, leeches, and marine worms. The general characteristics of an Annelid are similar to those of a roundworm; in that, they are bilaterally symmetrical, have tree germ layers, tube-within-a-tube body plan, and organs. However, an Annelid also has a true coelom, and segmentation, which both allow for greater specification of body parts. Septa are partitions between segments and allow structural support by creating a hydroelastic skeleton. The septa allow for specialized parts of the digestive system, which will be discussed in the anatomy of the earthworm later in this lesson. The excretory system consists of nephridia (filtering organ) in each segment. The Annelid moves by alternating contractions of circular and longitudinal muscles. The circular muscles encompass the body wall and therefore contractions cause the body to become long and thin. The longitudinal muscles run the length of the body, and cause the body to shorten and fatten.

The annelids include animals such as the earthworms, leeches, and marine worms. The general characteristics of an Annelid are similar to those of a roundworm; in that, they are bilaterally symmetrical, have tree germ layers, tube-within-a-tube body plan, and organs. However, an Annelid also has a true coelom, and segmentation, which both allow for greater specification of body parts. Septa are partitions between segments and allow structural support by creating a hydroelastic skeleton. The septa allow for specialized parts of the digestive system, which will be discussed in the anatomy of the earthworm later in this lesson. The excretory system consists of nephridia (filtering organ) in each segment. The Annelid moves by alternating contractions of circular and longitudinal muscles. The circular muscles encompass the body wall and therefore contractions cause the body to become long and thin. The longitudinal muscles run the length of the body, and cause the body to shorten and fatten.Mollusks

Adults are billaterally symmetrical. Bodies are divided into 3 parts: Head, Foot, and Visceral Hump. All organ systems present. A mantle (A thin membrane that secretes the calcium carbonate shell found in most mollusk species).Radula (A toung-like structure that "scrapes" for food.)

Adults are billaterally symmetrical. Bodies are divided into 3 parts: Head, Foot, and Visceral Hump. All organ systems present. A mantle (A thin membrane that secretes the calcium carbonate shell found in most mollusk species).Radula (A toung-like structure that "scrapes" for food.)Special Exhibition- Oysters

The common name oyster is used for a number of different groups of bivalve mollusks, most of which live in marine habitats or brackish water. The shell consists of two usually highly calcified valves which surround a soft body. Gills filter plankton from the water, and strong adductor muscles are used to hold the shell closed. Some types of oysters are highly prized as food, both raw and cooked. Other types, such as pearl oysters, are not commonly eaten. True oysters, belonging to the family Ostreidae, are incapable of making gem-quality pearls, although the opposite idea is a commonly-encountered misapprehension, often seen in illustrations or photographs where an edible oyster shell is mistakenly paired with a gem-quality pearl.

The common name oyster is used for a number of different groups of bivalve mollusks, most of which live in marine habitats or brackish water. The shell consists of two usually highly calcified valves which surround a soft body. Gills filter plankton from the water, and strong adductor muscles are used to hold the shell closed. Some types of oysters are highly prized as food, both raw and cooked. Other types, such as pearl oysters, are not commonly eaten. True oysters, belonging to the family Ostreidae, are incapable of making gem-quality pearls, although the opposite idea is a commonly-encountered misapprehension, often seen in illustrations or photographs where an edible oyster shell is mistakenly paired with a gem-quality pearl.Special Exhibition- Conch

A conch is one of a number of different species of medium-sized to large saltwater snails or their shells. True conchs are marine gastropod molluscs in the family Strombidae, and the genus Strombus. A conch's shell has a high spire and a noticeable siphonal canal. Other species often called a "conch" include the crown conch Melongena species; the horse conch Pleuroploca gigantea; and the sacred chank or more correctly Shankha shell, Turbinella pyrum. None of these are in the family Strombidae, but instead in other families of the molluscs.Another use, the conch in architecture refers to shells with a totally different scallop shape. The true conch species within the genus Strombus vary in size from fairly small to very large. Several of the larger species are economically important as food sources; these include the endangered queen conch or pink conch Strombus gigas, which very rarely may produce a pink, gem quality pearl. About 74 species of the Strombidae family are living, and a much larger number of species exist only in the fossil record. Of the living species, most are in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Six species live in the greater Caribbean region, including the Queen Conch, and the West Indian Fighting Conch, Strombus pugilis. Many species of conch live on sandy bottoms among beds of sea grass in warm tropical waters.

A conch is one of a number of different species of medium-sized to large saltwater snails or their shells. True conchs are marine gastropod molluscs in the family Strombidae, and the genus Strombus. A conch's shell has a high spire and a noticeable siphonal canal. Other species often called a "conch" include the crown conch Melongena species; the horse conch Pleuroploca gigantea; and the sacred chank or more correctly Shankha shell, Turbinella pyrum. None of these are in the family Strombidae, but instead in other families of the molluscs.Another use, the conch in architecture refers to shells with a totally different scallop shape. The true conch species within the genus Strombus vary in size from fairly small to very large. Several of the larger species are economically important as food sources; these include the endangered queen conch or pink conch Strombus gigas, which very rarely may produce a pink, gem quality pearl. About 74 species of the Strombidae family are living, and a much larger number of species exist only in the fossil record. Of the living species, most are in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Six species live in the greater Caribbean region, including the Queen Conch, and the West Indian Fighting Conch, Strombus pugilis. Many species of conch live on sandy bottoms among beds of sea grass in warm tropical waters.Special Exhibition- Octopus

The octopus is a cephalopod of the order Octopoda that inhabits many diverse regions of the ocean, especially coral reefs. The term may also refer to only those creatures in the genus Octopus. In the larger sense, there are around 300 recognized octopus species, which is over one-third of the total number of known cephalopod species. An octopus has eight flexible arms, which trail behind it as it swims. Most octopuses have no internal or external skeleton, allowing them to squeeze through tight places. An octopus has a hard beak, with its mouth at the center point of the arms. Octopuses are highly intelligent, probably the most intelligent invertebrates. They are known to build "forts" and "traps" in the wild, and for rearranging tanks and burying other animals alive in domestication. For this reason, they are quite notorious among aquarium operators. For defense against predators, they hide, flee quickly, expel ink, or use color-changing camouflage. Octopuses are bilaterally symmetrical, like other cephalopods, with two eyes and four pairs of arms. All octopuses are venomous, but only the small blue-ringed octopuses are deadly to humans

The octopus is a cephalopod of the order Octopoda that inhabits many diverse regions of the ocean, especially coral reefs. The term may also refer to only those creatures in the genus Octopus. In the larger sense, there are around 300 recognized octopus species, which is over one-third of the total number of known cephalopod species. An octopus has eight flexible arms, which trail behind it as it swims. Most octopuses have no internal or external skeleton, allowing them to squeeze through tight places. An octopus has a hard beak, with its mouth at the center point of the arms. Octopuses are highly intelligent, probably the most intelligent invertebrates. They are known to build "forts" and "traps" in the wild, and for rearranging tanks and burying other animals alive in domestication. For this reason, they are quite notorious among aquarium operators. For defense against predators, they hide, flee quickly, expel ink, or use color-changing camouflage. Octopuses are bilaterally symmetrical, like other cephalopods, with two eyes and four pairs of arms. All octopuses are venomous, but only the small blue-ringed octopuses are deadly to humansEchinoderm

Echinoderms and vertebrates are the only two groups of animals that are Deuterostomes. This means that the first embryonic opening becomes the anus and the second becomes the mouth. Because of this trait, it is thought that echinoderms are more advanced than some of the other animals. However, Echinoderms also have some less developed characteristics. For example, their radiometric symmetry would usually be considered more primitive than bilateral symmetry, so it is difficult to see their relation to the vertebrates. Also, echinoderms have no cephalisation, and have a nerve net for controlling motor and sensory functions. However, when in larval form, an echinoderm is a free swimming bilaterally symmetrical organism. It is this larval form that scientists believe evolved into some of the prochordates that are mentioned later in this unit. Echinoderms are fairly diverse in appearance within the phylum. Typified by the starfish (sea star), sea urchins, feather stars and sea cucumbers vary in outer appearance but are internally structured similarly. The digestive system is relatively short, and digestive glands are located within the arms of the starfish, or on the outer body wall of the other members. Digestion, however, is a bit different than other animals, in that, much of it takes place outside the body of the starfish. The echinoderm will put its stomach outside of its body and begin to digest its prey before it takes it in to finish the process. Sex organs are also located in the arms of the starfish, and echinoderms are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction. The regeneration properties of starfish allow them to regrow lost limbs as well as the limb regrowing a body. Respiratory organs, called skin gills, are found throughout the body wall providing the echinoderm with oxygen. The method of locomotion in the starfish is truly unique. The water vascular system is a network of tubes ending in tube feet. An organs called an ampula will pump water into the tubes increasing the pressure in tube feet causing it to expand and create a suction on a nearby surface. As the pressure on the tube foot decreases, the tube contracts without decreasing the suction, and the starfish is pulled in that direction.

Echinoderms and vertebrates are the only two groups of animals that are Deuterostomes. This means that the first embryonic opening becomes the anus and the second becomes the mouth. Because of this trait, it is thought that echinoderms are more advanced than some of the other animals. However, Echinoderms also have some less developed characteristics. For example, their radiometric symmetry would usually be considered more primitive than bilateral symmetry, so it is difficult to see their relation to the vertebrates. Also, echinoderms have no cephalisation, and have a nerve net for controlling motor and sensory functions. However, when in larval form, an echinoderm is a free swimming bilaterally symmetrical organism. It is this larval form that scientists believe evolved into some of the prochordates that are mentioned later in this unit. Echinoderms are fairly diverse in appearance within the phylum. Typified by the starfish (sea star), sea urchins, feather stars and sea cucumbers vary in outer appearance but are internally structured similarly. The digestive system is relatively short, and digestive glands are located within the arms of the starfish, or on the outer body wall of the other members. Digestion, however, is a bit different than other animals, in that, much of it takes place outside the body of the starfish. The echinoderm will put its stomach outside of its body and begin to digest its prey before it takes it in to finish the process. Sex organs are also located in the arms of the starfish, and echinoderms are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction. The regeneration properties of starfish allow them to regrow lost limbs as well as the limb regrowing a body. Respiratory organs, called skin gills, are found throughout the body wall providing the echinoderm with oxygen. The method of locomotion in the starfish is truly unique. The water vascular system is a network of tubes ending in tube feet. An organs called an ampula will pump water into the tubes increasing the pressure in tube feet causing it to expand and create a suction on a nearby surface. As the pressure on the tube foot decreases, the tube contracts without decreasing the suction, and the starfish is pulled in that direction.Special Exhibition- Clown of Thorns

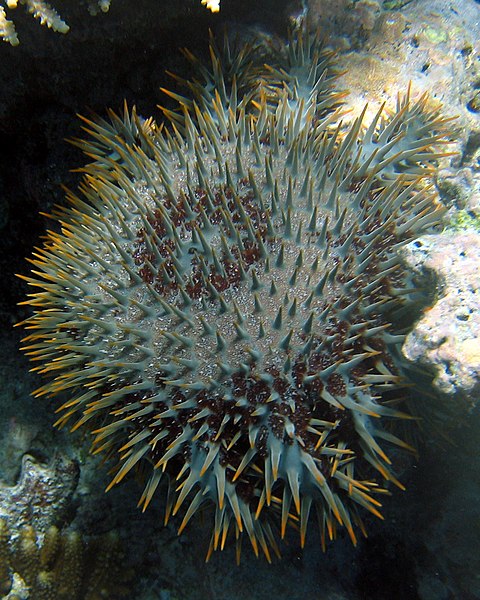

he Crown-of-Thorns Starfish is a large nocturnal sea star that preys upon coral polyps. The crown-of-thorns receives it name from venomous thorn-like spines that cover its body. The Crown-of-Thorns is endemic to tropical coral reefs in the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean. Solitary animals, they feed alone and maintain constant distance between themselves and other members of their species. The Crown-of-Thorns is the second largest sea star in the world. Only the Giant Sunstar is larger.

he Crown-of-Thorns Starfish is a large nocturnal sea star that preys upon coral polyps. The crown-of-thorns receives it name from venomous thorn-like spines that cover its body. The Crown-of-Thorns is endemic to tropical coral reefs in the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean. Solitary animals, they feed alone and maintain constant distance between themselves and other members of their species. The Crown-of-Thorns is the second largest sea star in the world. Only the Giant Sunstar is larger.Special Exhibition- Sea Urchins

Sea urchins are small, spiny, globular creatures that compose part of class Echinoidea. They are found in oceans all over the world. Their shell, or "test", is round and spiny, typically from 3 to 10 cm across. Common colors include black and dull shades of green, olive, brown, purple, and red. They move slowly, feeding mostly on algae. Sea otters, wolf eels, and other predators feed on urchins. Sea urchins are harvested and served as a delicacy. Sea urchins are members of the phylum Echinodermata, which also includes sea stars, sea cucumbers, brittle stars, and crinoids. Like other echinoderms they have fivefold symmetry and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive "tube feet". The pentamerous symmetry is not obvious at a casual glance but is easily seen in the dried shell or test of the urchin. Together with sea cucumbers, they make up the subphylum Echinozoa, which is defined by primarily having a globoid shape without arms or projecting rays. Sea cucumbers and the irregular echinoids have secondarily evolved different shapes. Although many sea cucumbers have branched tentacles surrounding the oral opening, these have originated from modified tube feet and are not homologous to the arms of the crinoids, sea stars and brittle stars.

Sea urchins are small, spiny, globular creatures that compose part of class Echinoidea. They are found in oceans all over the world. Their shell, or "test", is round and spiny, typically from 3 to 10 cm across. Common colors include black and dull shades of green, olive, brown, purple, and red. They move slowly, feeding mostly on algae. Sea otters, wolf eels, and other predators feed on urchins. Sea urchins are harvested and served as a delicacy. Sea urchins are members of the phylum Echinodermata, which also includes sea stars, sea cucumbers, brittle stars, and crinoids. Like other echinoderms they have fivefold symmetry and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive "tube feet". The pentamerous symmetry is not obvious at a casual glance but is easily seen in the dried shell or test of the urchin. Together with sea cucumbers, they make up the subphylum Echinozoa, which is defined by primarily having a globoid shape without arms or projecting rays. Sea cucumbers and the irregular echinoids have secondarily evolved different shapes. Although many sea cucumbers have branched tentacles surrounding the oral opening, these have originated from modified tube feet and are not homologous to the arms of the crinoids, sea stars and brittle stars.Special Exhibition- Sea Cucumber

Holothuroidea are a class of marine animals (phylum Echinodermata) with an elongated body and leathery skin, which is found on the sea floor worldwide. Many holothurian species and genera, informally known as sea cucumbers, are targeted for human consumption. The harvested product is also known as trepang, bêche-de-mer, balate, or sea slug. The body contains a single, branched gonad. Like all echinoderms, sea cucumbers have an endoskeleton just below the skin, calcified structures that are usually reduced to isolated microscopic ossicles (or sclerietes) joined by connective tissue. These can sometimes be enlarged to flattened plates, forming an armour. In pelagic species such as Pelagothuria natatrix (Order Elasipodida, family Pelagothuriidae), the skeleton and a calcareous ring are absent.

Holothuroidea are a class of marine animals (phylum Echinodermata) with an elongated body and leathery skin, which is found on the sea floor worldwide. Many holothurian species and genera, informally known as sea cucumbers, are targeted for human consumption. The harvested product is also known as trepang, bêche-de-mer, balate, or sea slug. The body contains a single, branched gonad. Like all echinoderms, sea cucumbers have an endoskeleton just below the skin, calcified structures that are usually reduced to isolated microscopic ossicles (or sclerietes) joined by connective tissue. These can sometimes be enlarged to flattened plates, forming an armour. In pelagic species such as Pelagothuria natatrix (Order Elasipodida, family Pelagothuriidae), the skeleton and a calcareous ring are absent.